My experiences of conducting a research project in India

Georgia Hales, Graduate, Master of Engineering (Civil and Environmental).

*This post is about research conducted as part of a Master of Engineering (Civil and Environmental Engineering) final project, supervised by Dr Dani Barrington*

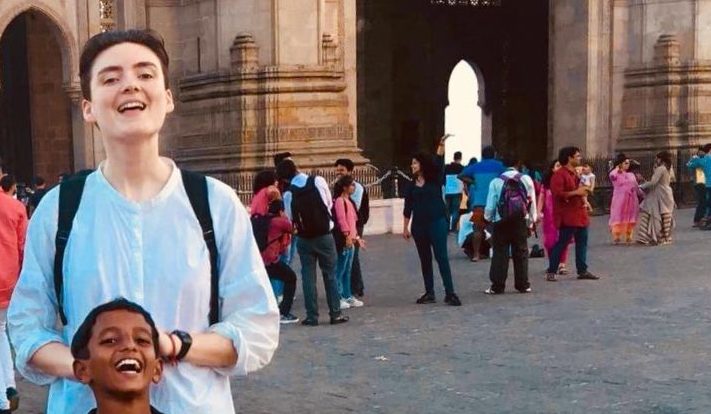

In March/April 2018 I went to Mumbai, India, to interview schoolteachers about what was being taught to schoolboys on menstrual hygiene management (MHM), as part of my Masters degree in Civil and Environmental Engineering. I had never been to India before, but had heard lots of accounts from female friends that had been travelling there of harassment and unwanted attention. Having shaved my head the previous summer, being flat-chested, dark haired and half a foot above the average height for a British girl, being mistaken for a boy was a weekly occurrence for me where I lived in Leeds. I thought I would use this as a sort of secret super-power whilst in India by pretending to be a boy in order to (hopefully) receive less hassle and more respect. Having only been groped twice whilst I was there, I’d like to think it worked. A few other challenges arose with this, however, the first being which train carriage to use (them being segregated for the safety of women). At first, staying in character, I chose the male carriage. Although the men seemed unphased, I felt slightly ill at ease being the only white female in a carriage packed full of Indian men. On the way back I chose to go in the women’s carriage. This proved to be worse as I was very aware of how uncomfortable I was making the women, with them thinking I was a white man. I tried to present myself more femininely in the way I moved and sat (pushing out my chest as much as I could) and smiled at them so that they would realise I was actually a woman and not a threat. After a while, they returned my smiles and seemed more at ease with me.

For the research, I had initially set out to interview both male and female teachers in order to get a more rounded view of the situation. This proved difficult, however, as upon arrival at the schools and seeing me (a confusing boy/girl mashup), the two women who were accompanying me to translate and hearing the nature of the subject, the male teachers refused to be interviewed and would pass us on to female teachers instead. Although frustrating, it was useful in helping me to gain an insight into the common male attitudes of menstruation in India: fear, repulsion and rejection. Eventually we convinced one man to be interviewed by us, with his proviso that he could have a female teacher to chaperone him. This was of course fine by us, except for the fact that she kept answering questions for him, such as saying ‘yes, yes!’ enthusiastically to the question ‘would you feel comfortable teaching your students about the subject?’ when his answer was actually a ‘no, no’. Ironically during this interview I was on my period and was feeling as though I might be leaking. Feeling a sudden and emotional sense of connectedness and understanding with the struggles of all of the schoolgirls that were the subject of my research, I decidedly knew that if I had leaked I would wear my blood with pride as I marched through the school to the toilet – assuring my gender to the children who were on the fence in deciding if it was a foreign ‘bhai’ (brother) or ‘didi’ (sister) visiting their school. It turned out to be fine and I got to see what the toilet facilities were like. They were basic, but ok. I wasn’t sure if there were different toilets for boys and girls but there were private cubicles over a squat toilet with a lock on the door and a bucket and tap for cleaning and flushing, though no soap, light, sanitary bin or mirror could be seen.

For the six weeks I was in Mumbai I was staying with my cousin and so would go out with her and her friends in the evenings and weekends. Naturally her friends, acquaintances and other people we met whilst we were out (a mix of foreigners, Indians and locals, all well educated and fluent in English) asked me what I was doing in Mumbai. When broaching the subject, every Indian (male and female) would shake their head in despair at the state of the education on menstruation, explaining how they got next to no information when they were younger and how they still believe that to be the case in most state schools across the country. One woman I made friends with even told me about how when she was younger she remembers her mother being forced to sleep outside the house when she was on her period. I was grateful for everyone being so willing to share their experiences with me, however one evening, when I was in the queue for the toilet, I got talking to one man who seemed to know a lot about the subject. He said that he was friends with Arunachalam Muruganantham, the Indian activist who invented a simple, low cost machine that creates sanitary pads for women in poorer, rural areas, made famous by the Bollywood movie ‘Padman’. He could see that I was very excited by this and suggested that he could put me in contact, to which I was thrilled. As the conversation continued, however, I started to realise that although he seemed to know a lot, he was still a man intent on telling me “what’s what”. First of all, he ‘man-splained’ my whole thesis to me (very helpful…), then told me that everything I was doing was futile as ‘nothing will ever change’ and then repeatedly told me I was an ‘outsider’ that will ‘never understand’, all the while pushing me on my shoulders. Thankfully he did reassure me that he wasn’t being patronising or aggressive. I responded by saying that it was ironic that he thought the situation was never going to change, as it was his supposed friend Padman that had encouraged the pad distribution schemes in all the schools I visited (succeeding in keeping the girls in school), it is him that would never understand the situation – as my supervisor quite rightly put ‘if you don’t have a vagina, you’ll never understand’. The conversation ended with him saying that unfortunately he can’t put me in contact with Padman – he is of course a very busy man helping (and succeeding) in progressing India’s relationship with menstrual hygiene management.

For the six weeks I was in Mumbai I was staying with my cousin and so would go out with her and her friends in the evenings and weekends. Naturally her friends, acquaintances and other people we met whilst we were out (a mix of foreigners, Indians and locals, all well educated and fluent in English) asked me what I was doing in Mumbai. When broaching the subject, every Indian (male and female) would shake their head in despair at the state of the education on menstruation, explaining how they got next to no information when they were younger and how they still believe that to be the case in most state schools across the country. One woman I made friends with even told me about how when she was younger she remembers her mother being forced to sleep outside the house when she was on her period. I was grateful for everyone being so willing to share their experiences with me, however one evening, when I was in the queue for the toilet, I got talking to one man who seemed to know a lot about the subject. He said that he was friends with Arunachalam Muruganantham, the Indian activist who invented a simple, low cost machine that creates sanitary pads for women in poorer, rural areas, made famous by the Bollywood movie ‘Padman’. He could see that I was very excited by this and suggested that he could put me in contact, to which I was thrilled. As the conversation continued, however, I started to realise that although he seemed to know a lot, he was still a man intent on telling me “what’s what”. First of all, he ‘man-splained’ my whole thesis to me (very helpful…), then told me that everything I was doing was futile as ‘nothing will ever change’ and then repeatedly told me I was an ‘outsider’ that will ‘never understand’, all the while pushing me on my shoulders. Thankfully he did reassure me that he wasn’t being patronising or aggressive. I responded by saying that it was ironic that he thought the situation was never going to change, as it was his supposed friend Padman that had encouraged the pad distribution schemes in all the schools I visited (succeeding in keeping the girls in school), it is him that would never understand the situation – as my supervisor quite rightly put ‘if you don’t have a vagina, you’ll never understand’. The conversation ended with him saying that unfortunately he can’t put me in contact with Padman – he is of course a very busy man helping (and succeeding) in progressing India’s relationship with menstrual hygiene management.